- Home

- Dan Ryckert

The Dumbest Kid in Gifted Class

The Dumbest Kid in Gifted Class Read online

by Dan Ryckert

©2016 Up To Something Publishing

Foreword

by Tim Turi

“Dan is a liar.”

I remember the first time I heard someone whisper those words to me in the Game Informer vault, surrounded by a treasure trove of video games numbering in the thousands. I hadn’t paused to consider that Dan might be a compulsive fibber before that moment, but that explanation to his bombastic persona suddenly seemed so obvious.

Dan Ryckert and I signed our papers to join the Game Informer team and begin our dream jobs on the very same day. The ink was barely dry before he began regaling the staff – unsolicited – with myriad stories about his adventures growing up in Kansas. His unassuming demeanor made each yarn even more unbelievable. Dan’s an average dude with glasses, a Thin Lizzy shirt, and a worn pair of Adidas. But somehow, at age 19, he was savvy enough to con GameStop businessmen into paying him to create an in-store commercial – all so he could fly out to GI’s offices and plant the seed for his eventual employment while running around in a shark suit.

Dan would begin talking, wide-eyed with enthusiasm and gesticulating wildly as he recounted story after story. The hits kept coming: The time he found himself in a car next to funk mastermind George Clinton and Eddie Winslow from Family Matters. How he had uploaded a compromising video of Kansas City Royals legend George Brett talking about shitting his pants, which became an internet phenomenon.

Over time these tales were met with amusement, inquisition, interrogation, and eventually disbelief. I can practically hear Game Informer’s Joe Juba murmuring “uh huh” in his dry deadpan and walking away with his arms folded across his chest after hearing Dan’s latest.

How could this Dan guy, whose culinary peak was a bottle of Mickey’s and cheap Fettuccini Alfredo somehow have had more excitement in his life by age 25 than most find in a lifetime?

I admit, even I had my reservations, despite Dan and me quickly bonding over classic rock, a shared appreciation of awful video games, and the mutual understanding that Terminator 2 is perhaps the perfect film. But my doubts about Dan’s raucous Kansas past faded to the background as we became close friends. Coming out of a bad breakup, I discovered a source of much-needed kinship and distraction in him, as I ended up in situations uncharacteristic for me.

Suddenly, I found myself standing at the open hatch of an airplane, wind whipping through my hair as I wondered how he had persuaded me into skydiving. I watched in disbelief as an office argument we began over boneless vs. bone-in buffalo wings erupted into a global Twitter debate – all thanks to Dan’s knack for spin – culminating in culinary tastemaker Anthony Bourdain concluding that boneless wings are “a sin against god” (he’s right, #TeamBoneIn 4 life).

I sat in bewilderment as Dan led rap artist/reality TV star Riff Raff out of a hotel and crammed him and his hulking bodyguard into my tiny Toyota Corolla so we could all play ToeJam & Earl in Panic on Funkotron.

The point is that I think it’s natural to see someone like Dan – a fiercely “normal” guy – and wonder how his life could be so chock full of extraordinary events. Anyone who tunes into Dan on Giant Bomb, has heard him on old episodes of Game Informer’s Replay, or listens to his stories over a beer or two, would be within their rights to question what they’ve heard.

The thing is, as I learned through firsthand experience, if you stick with Dan long enough you see these things happen before your very eyes. Whether you live some of these remarkably lucky encounters alongside Dan, like I have, or see the zaniness pop up on your Twitter feed, enough evidence mounts to reinforce Dan’s crazy, charmed life.

One crucial factor separates Dan and I when reflecting back on our weird antics: Dan has a special way with words. He is perhaps the best storyteller I’ve ever met, making a conversation about the most mundane facets of life – scrambling egg whites, for example – enthralling and hilarious.

So it stands to reason that a collection of his stories will undoubtedly entertain. My recommendation after over 8 years with this guy as one of my best friends: strap in and enjoy the ride.

Oh, and remember one thing: It’s true. All of it.

Dedicated to Bianca

Blood on the Sand

Elementary school kids typically don’t have strong opinions regarding their choice of deity. A couple of folks give birth to you, and your early years come with an assortment of grandfathered-in opinions on religion and politics and everything in between. At Holy Trinity Elementary School in Lenexa, Kansas, this led to an entire building filled with kids who proudly wore Catholicism on their sleeves and really hated Bill Clinton.

I was by no means a hard-nosed atheist growing up—that period took place during an especially obnoxious six months or so in college—but I didn’t have strong opinions when it came to the big questions of the universe. Considering that Holy Trinity was an expensive private Catholic school, not a lot of parents sent their kids there unless the whole God thing was particularly important to them. My parents and I were not weekly churchgoers unlike virtually all of my classmates. I attended Holy Trinity solely because my grandparents had money and they were adamant about me being raised Catholic. When they offered to bankroll the tuition costs, my parents shrugged their shoulders and went along with it.

Kids at this school were 100 percent invested in the religion thanks to their parents’ status as devout members of the church. I felt like I was the only one who didn’t genuinely enjoy going to school Mass every Tuesday, saying full rosaries during class, and confessing sins to priests several times a year. It’s not that I hated these activities; I just viewed them in the same way I viewed any other avenue of schoolwork: it was boring and I couldn’t wait for it to be over.

I once overheard a group of my classmates swearing up and down that communion wafers would bleed if they were cut in two. These magic wafers were made up of the literal, for-real corpse of Jesus; surely this made sense. I was skeptical, so I ran a little experiment after one of our Tuesday Masses.

When it came time for the priest to place the wafer on my tongue, I quickly moved it between my teeth and did my best to keep it dry. I performed the sign of the cross and headed back to my seat in the pew. There, I retrieved the mostly dry wafer from my mouth and stealthily moved it to my front pocket while pretending to be deep in prayer with the rest of the class. Once Mass was done, I shifted the wafer to the middle of my spiral notebook to make sure it stayed intact until I got to my grandmother’s house that afternoon.

In the 25 years I spent with my grandmother, I can barely remember any instances of her being even slightly mad at me. There was that one time she yelled at me in the car for being a little shit while sledding with my cousins, but that’s about it. When she walked into her kitchen to see me holding a knife over a split communion wafer, she ranted and raved and yelled enough to make up for a quarter century of total benevolence toward me.

It didn’t bleed, by the way.

My father never talked about religion at all during my youth, and I can only remember one time that my mother and I discussed anything on the topic. After catching myself muttering “Jesus Christ!” in vain while dying in a video game, I went downstairs to ask her if I’d be irrevocably condemned to hell as a result.

“Eh, I don’t think so,” she said. “You’ll still go to heaven if you’re a good person, but I don’t think there are a bunch of dead people walking around and talking to each other.”

That was the first time I had any questions about religion, which was a subject taught right alongside math, science, and English at Holy Trinity. As I got older, questions started bouncing around in my head more frequently. During one religion class, I

caught myself ruminating on one thought. I approached my teacher after the school day was over.

“Mrs. Herding, I have a question.”

“What’s that, Danny?”

“We know for sure that Jesus Christ is the son of God and that everything we learn about in class is how things really are, right?”

“Yes.”

“But what about the other religions? People that believe in those probably believe that their god is the real god just as much as we believe ours is, right?”

“Yes.”

“We can’t all be right, though. So we know for sure that we’re the right one?”

“Yes.”

“Alright, thanks!”

I wasn’t particularly sold, but her confidence assured me that the conversation wouldn’t progress past that point.

Despite my questions about religion, my lack of opinion on the subject was far from the biggest reason that I didn’t fit in at Holy Trinity. Put as generally as possible, I was a weird-ass kid. Video games and professional wrestling were the two things in the world that I cared about, and it seemed impossible to find anyone who wanted to discuss either topic.

I hit a brick wall at recess when I wanted to talk to anyone about how crazy it was that Diesel won the WWF title from Bob Backlund at a house show. Blank stares were the only reaction when I excitedly relayed the information that Chuck Norris helped The Undertaker at Survivor Series by kicking Jeff Jarrett in the chest. Nothing in the world seemed cooler than this, so why did everyone prefer to talk about boring stuff like the Kansas City Chiefs or Jesus?

In third grade, I became aware of another amazing thing that was roundly ignored by most of my classmates. My grandmother would pick me up every Wednesday after school and take me to my uncle’s gas station. He had a rotating selection of games in the building, usually consisting of two arcade cabinets and one pinball machine. I spent a lot of time with classics there: the Simpsons arcade game, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the Terminator 2 and Addams Family pinball cabinets, and others. After a few months of this weekly tradition, a new game arrived at the gas station that was unfathomably cool to my eight-year-old brain.

My grandmother sat in the car while my cousin and I went into the gas station with our quarters. As I walked in, I saw two teenagers standing in front of a cabinet that I didn’t recognize. The fact that they were teenagers was scary enough, and they became even more intimidating when one of them complained that they lost due to “fucking computer shit.” These weren’t just teenagers. They were cussing teenagers. They might as well have had shivs and assault rifles strapped to their chests as far as I was concerned.

I found a table that was far enough away to feel safe from the teenage menaces, but still close enough to see the screen. Witnessing blood erupt out of the fighters’ heads every time they were punched was immediately captivating, but what really made me lose my mind was seeing a man’s head get punched clean off his shoulders. Afterward, the deliverer of the punch pumped his fist in celebration, put on sunglasses, and crossed his arms triumphantly. I didn’t know what I was seeing, but I had no doubt that it was the newest, coolest thing on the planet.

My cousin Matt noticed my open-mouthed reactions to everything I was seeing and expressed surprise that this was my first encounter with the game.

“You haven’t played Mortal Kombat yet?” he asked.

“No! How long has this been out?”

“About a month. I know all the secrets if you wanna see the fatalities.”

We had about an hour to play before my grandma took us home. I told Matt that he had to teach me absolutely everything he knew about this magical game. During my crash course, he taught me how to throw Scorpion’s spear, bombard enemies with Liu Kang’s fireballs and flying kicks, and spam Sub-Zero’s freeze-uppercut-slide combo. As great as those moves were, nothing compared to the moment after the fight was over. Whenever the “Finish Him!” prompt appeared and the screen darkened subtly, I felt like I was about to see something that I wasn’t supposed to see. Video games weren’t about heads being punched off and bodies being burnt to their skeletons; they were about jumping on some things and collecting a bunch of other things. When Matt was inputting a button sequence for a fatality, I felt like I should glance over my shoulder to ensure that my grandma or any of the gas station patrons weren’t within line of sight of the dark arts playing out on screen.

Each of the seven fatalities (well, six if we’re not counting Liu Kang’s bullshit cartwheel) burned into my brain. The next day, all I wanted to do was spread the good word of Mortal Kombat to everyone at school. I’d surely be a celebrated messenger, opening the eyes of my classmates to this amazing secret that none of them were aware of.

As soon as recess started, I bounced around from the basketball court to the kickball area to the kids with jump ropes, regaling them with stories of the glorious things I’d seen.

“Kano punches through the other dude’s chest, then pulls his heart out and holds it up and blood drips everywhere!”

“Scorpion is a teleporting ninja and he pulls his mask off and it’s just a skull underneath, and then he can breathe fire!”

“You can rip a dude’s head off and see his spine hanging out!”

Reactions ranged from apathy to revulsion, making me feel like I was surrounded by insane people. Were they hearing what I was saying? The spine was attached. You can pull a guy’s head off and his spine dangles down from the neck hole. This was all a real thing that could happen in a video game. How were my classmates not immediately abandoning recess and marching en masse to my uncle’s gas station?

No amount of enthusiasm could properly relay my excitement to others, squashing my desire to convert them into fellow Mortal Kombat devotees. During religion class that day, I ignored my teacher entirely as I pulled out my colored pencils and spiral notebook. I drew Raiden first, arcing his lightning toward a blank space that used to be Johnny Cage’s head. After filling in Cage’s legs and torso, I broke out the red colored pencil and drew a geyser of blood that made the actual game’s spray seem modest. With roughly 40 percent of my page covered in red pencil, I looked up to see my teacher standing over me with a very concerned look on her face.

By the end of the day, I found myself in the office of Principal Weber for the second time in my elementary school career. He wanted me to know in no uncertain terms that it wasn’t right to be drawing images like that, and he was concerned about my interest in something so violent. Enjoying Mortal Kombat must have been heresy to the staff of Holy Trinity, considering that a class meeting was called the year prior to inform us that we were forbidden to discuss “a popular television program with Beavis in the title, and another part of the title that will never be said within these walls.”

My reputation as a weird kid persisted throughout my kindergarten-to-fifth grade history in Catholic school. As time went on, I felt increasingly different from everyone else my age. I thought I was being funny when we practiced singing “Silent Night” for the annual Christmas program, but I sang it in Bob Dylan’s voice. It didn’t take long to realize that few children in the early ‘90s had any idea who Bob Dylan was.

I grew to resent and dislike my peers because of how different they were from me, and I was certain that everything they liked was wrong. Things came to a head in fifth grade as my behavior, interests, and sense of humor continued to be at odds with the rest of the class.

I was far from athletic and had no interest in sports. Understandably, I was always picked last for any team-based physical challenge. I never knew what I was doing when a ball came my way or when it was my turn to kick a thing. This was a conservative Catholic school in Kansas, so my classmates concluded that I clearly had to be gay. In that environment in that time period, “you’re gay” was the only insult that boys gave to other boys. Occasionally, you’d hear someone call you an idiot or a weirdo or whatever, but “you’re gay” was the clear favorite among Midwestern Catholic kids. I liked playing

Super Mario Kart more than I liked talking about football, so obviously this meant that I was sexually attracted to men. Whenever I missed a free throw in basketball or let another goal whiz by my uninterested head while playing goalie in soccer, there were always three or four classmates ready to yell “faggot!” When I couldn’t finish the mile run before class was over, it was probably because I was too busy thinking about all the penises I’d get to see when I was older.

This was confusing to me for a few reasons. The first is because I’m straight. The second is because I didn’t think that sexual orientation was determined by athletic prowess. The third is because I hadn’t gone to church enough to hear about how being gay was supposedly evil, so I didn’t even understand why it was an insult.

Unsurprisingly, I had learned about homosexuality as a result of watching professional wrestling. My education happened during a match between a sexually ambiguous character named Goldust (who resembled a living Oscar statuette, gold face paint and all) and Razor Ramon, a traditionally macho dude who talked like Tony Montana and had phrases like “Oozing Machismo” emblazoned on his merchandise. Goldust was “playing mind games” with Razor by grabbing his crotch and being overtly sexual, and Razor would react with horror whenever a golden gloved hand would come within a foot of his genital area.

“What’s going on here?” I asked my mom.

“Oh, Goldust is gay.”

“What does gay mean?”

“He wants to kiss guys instead of girls.”

“Oh, okay.”

That was the extent of it. No condemnation of Goldust’s lifestyle or sermons about Leviticus, just “he likes dudes” and that was that. As a result, I never attached any negative connotations to homosexuality, even when I was surrounded by the total opposite mindset every time I stepped on the playground.

The Dumbest Kid in Gifted Class

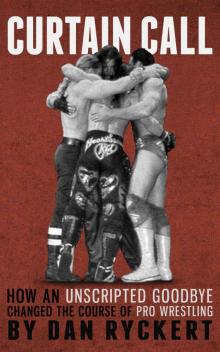

The Dumbest Kid in Gifted Class Curtain Call: How An Unscripted Goodbye Changed The Course Of Pro Wrestling

Curtain Call: How An Unscripted Goodbye Changed The Course Of Pro Wrestling